Purpose

tsgp is a lightweight package for modelling univariate

time-series data with Gaussian processes (GP). It is important to

remember that using a GP for time series basically converts the problem

from one of modelling a generative process (e.g., if we used an

ARIMA

model) to that of essentially a curve-fitting exercise. GPs are a Bayesian

method, so if you are unfamiliar with Bayesian inference, please go

check out some resources on that, such as this

great video by Richard McElreath. Essentially, the key bits to

remember for this post is that in Bayesian inference, we are interested

in the posterior distribution, which is proportional to the product of

the prior (our beliefs about an event before seeing the data) and the

likelihood (the probability of the data given model parameters).

If you would like a deeper treatment of how GPs can model time-series data, please see this post.

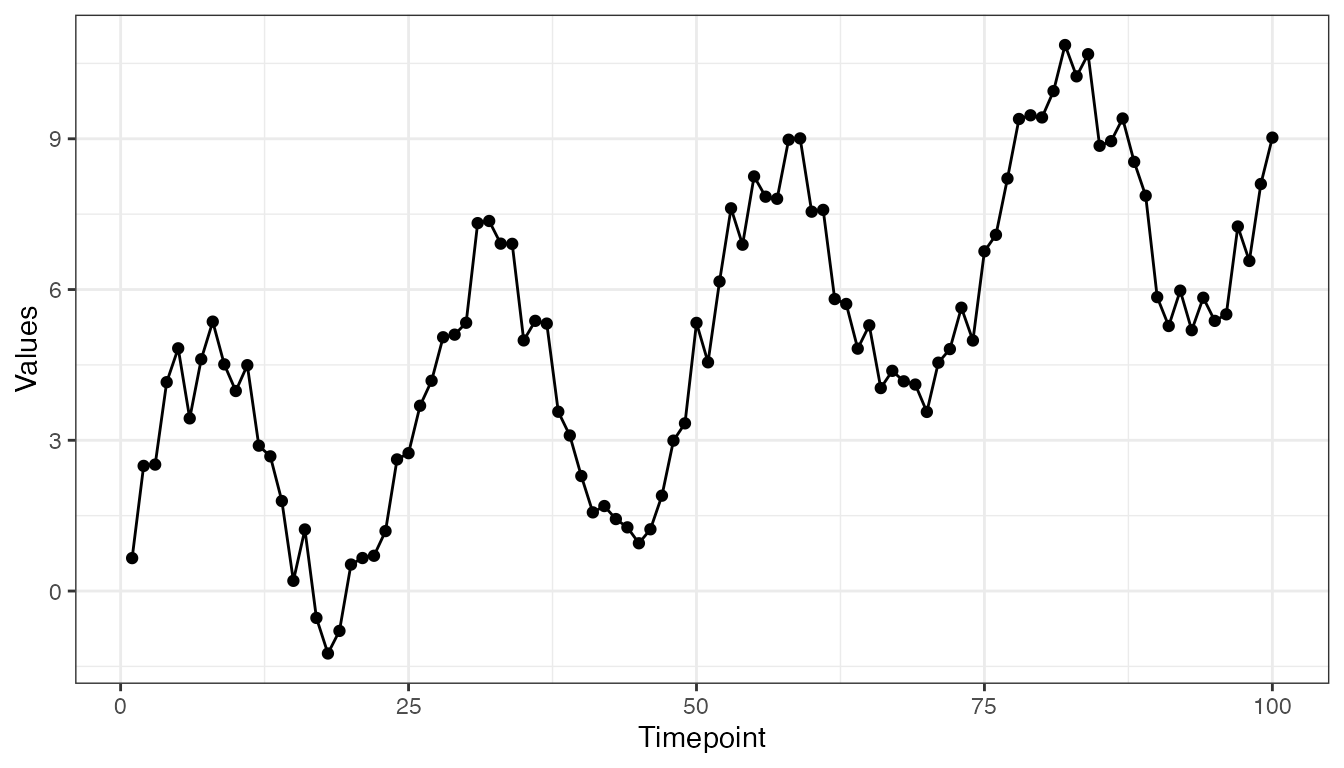

Generating some data

We are going to simulate some time series data with temporal dynamics that are commonly encountered in applied settings. Specifically, we are going to generate a noisy sine wave (i.e., to emulate periodic or seasonal data) with a linearly increasing trend:

set.seed(123)

y <- 3 * sin(2 * seq(0, 4 * pi, length.out = 100)) + runif(100) * 2

trend <- 0.08 * seq(from = 1, to = 100, by = 1)

y <- y + trend

tmp <- data.frame(timepoint = 1:length(y), y = y)

x1 <- 1:length(y)

# Draw plot

ggplot(data = tmp) +

geom_point(aes(x = timepoint, y = y), colour = "black") +

geom_line(aes(x = timepoint, y = y), colour = "black") +

labs(x = "Timepoint",

y = "Values") +

theme_bw()

Package functionality

Covariance functions

tsgp contains several covariance functions (coded in C++

for efficiency). All of them return an object of class

GPCov (which is just a matrix but with a new inherited

class that allows us to make use of R’s generic functions).

Exponentiated quadratic

\[ k(x, x') = \text{exp} \left( -\frac{1}{2\sigma^{2}}||x - x'||^{2} \right) \]

In tsgp, cov_exp_quad takes the following

arguments:

-

xa— vector of values -

xb— vector of values -

sigma— scalar denoting the variance. Defaults to1 -

l— scalar denoting the lengthscale. Defaults to1

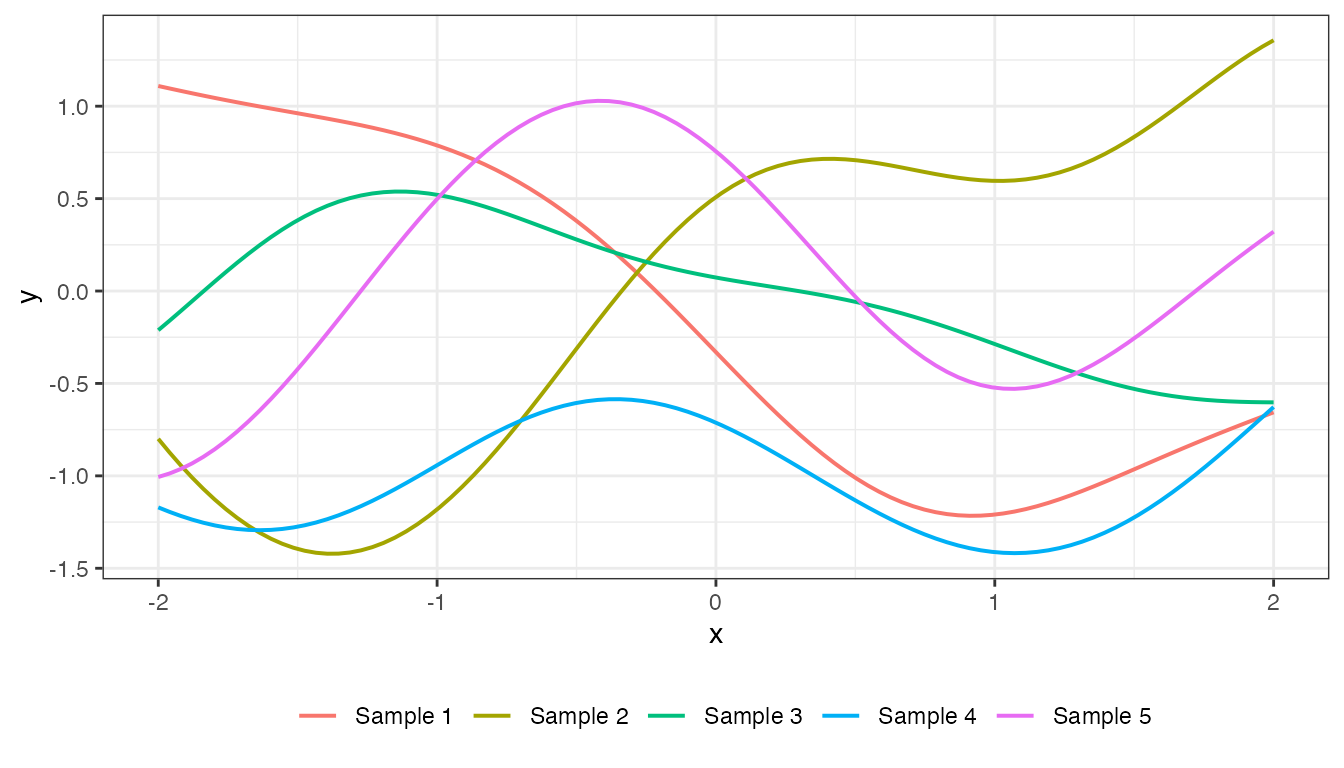

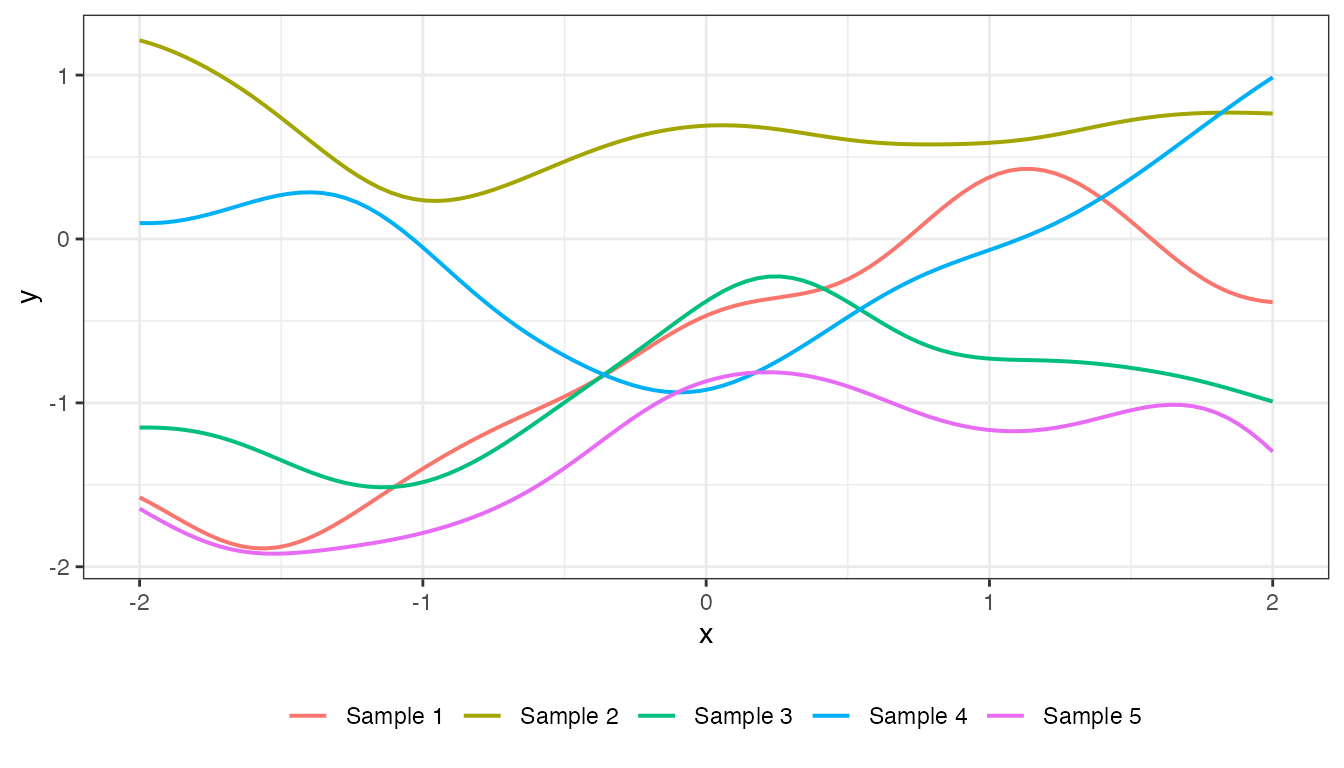

We can produce two types of plots for GPCov objects by

calling the plot() generic. The first is a plot of samples

from the prior distribution, which we specify by setting

type = "prior", passing in the input vector

(x2 in this example), and setting the number of samples to

draw through the argument k. Here is an example:

x2 <- seq(from = -2, to = 2, length.out = 100)

mat_exp_quad <- cov_exp_quad(x2, x2, 1, 1)

plot(mat_exp_quad, x2, type = "prior", k = 5)

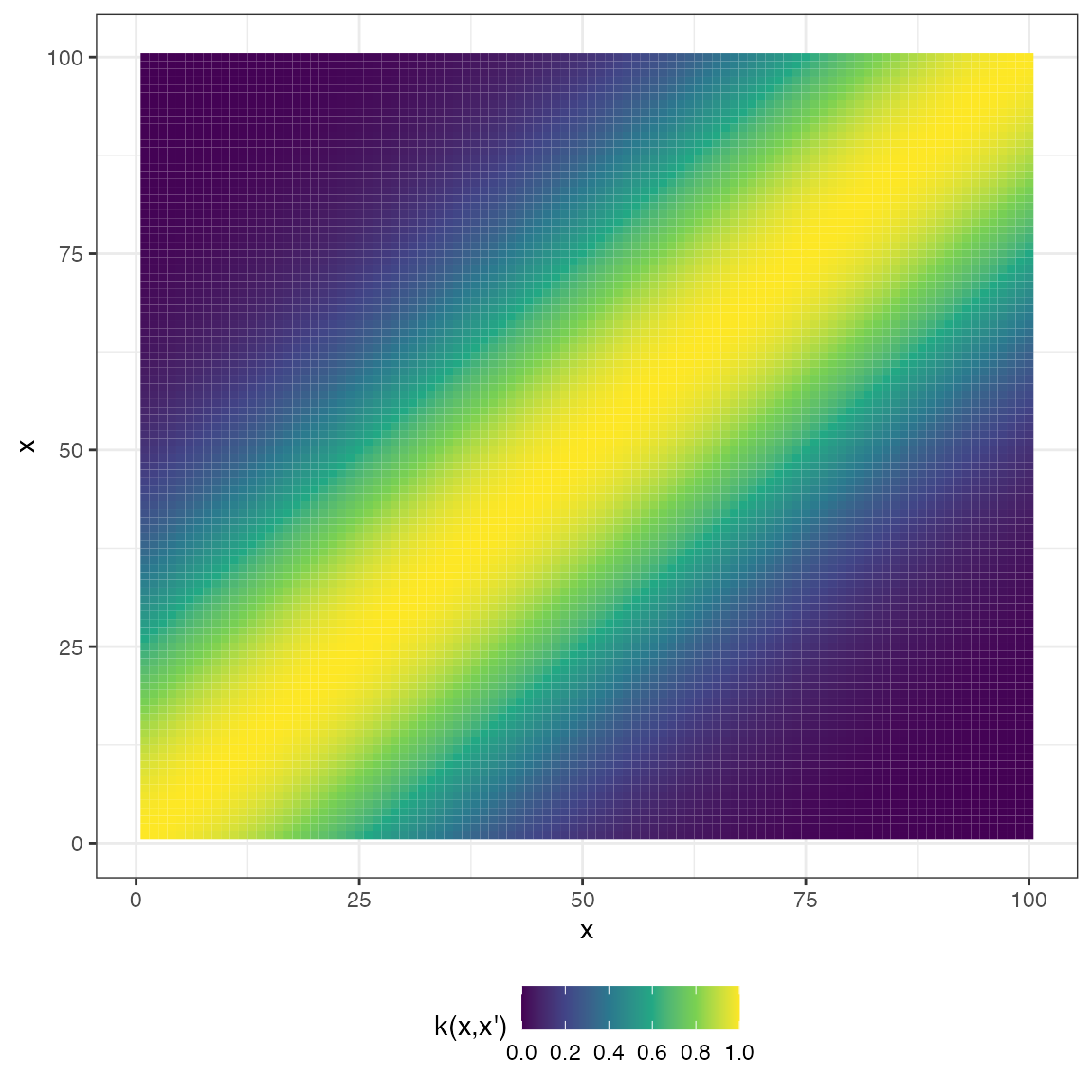

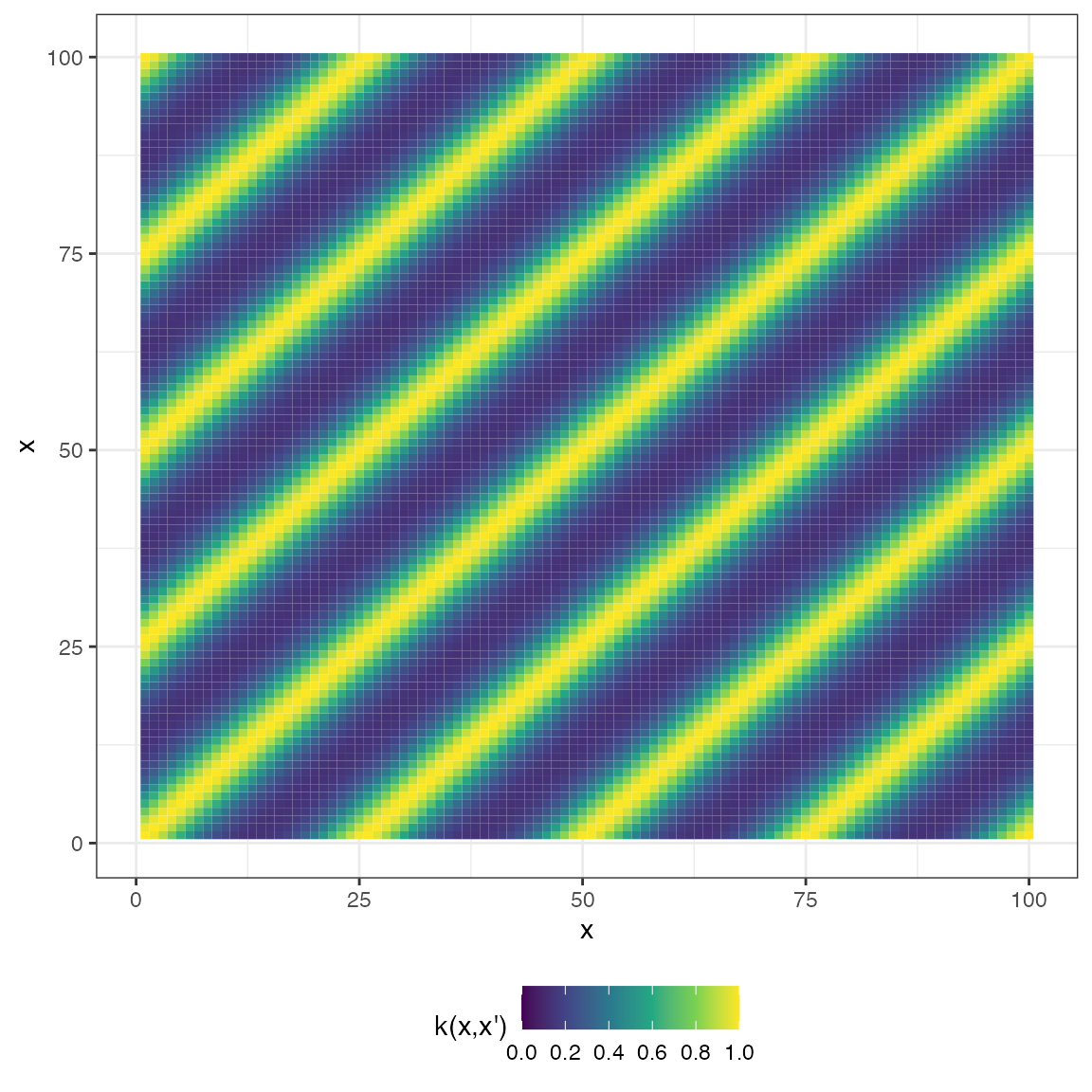

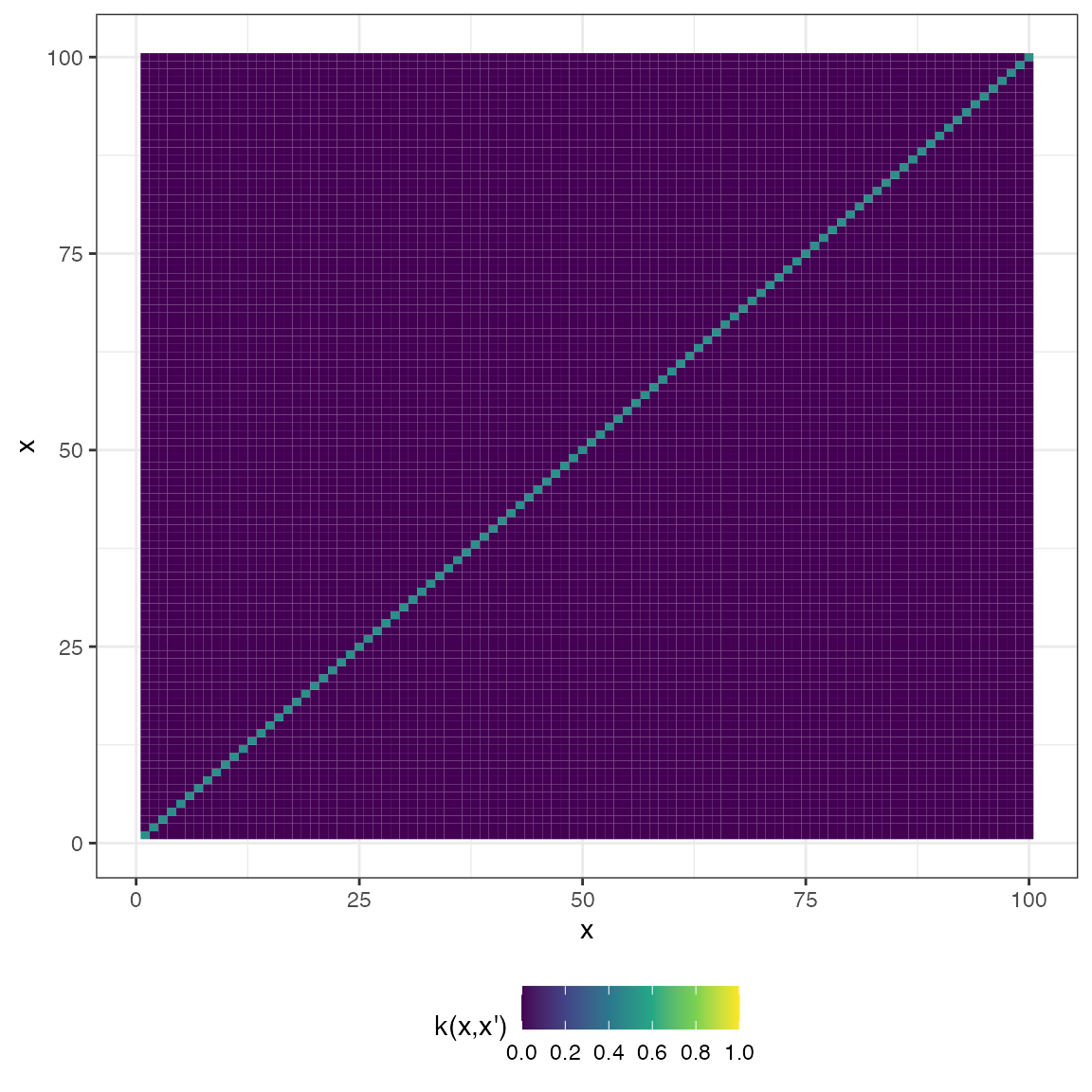

The second is a plot of the covariance matrix represented as a heatmap:

plot(mat_exp_quad, type = "matrix")

Rational quadratic

\[ k(x, x') = \sigma^{2} \left( 1 + \frac{||x - x'||^{2}}{2\alpha \mathcal{l}^{2}} \right)^{-\alpha} \]

In tsgp, cov_rat_quad takes the following

arguments:

-

xa— vector of values -

xb— vector of values -

sigma— scalar denoting the variance. Defaults to1 -

alpha— scalar \(>0\) denoting the mixing coefficient. Defaults to1 -

l— scalar denoting the lengthscale. Defaults to1

mat_rat_quad <- cov_rat_quad(x2, x2, 1, 1, 1)

plot(mat_rat_quad, x2, type = "prior", k = 5)

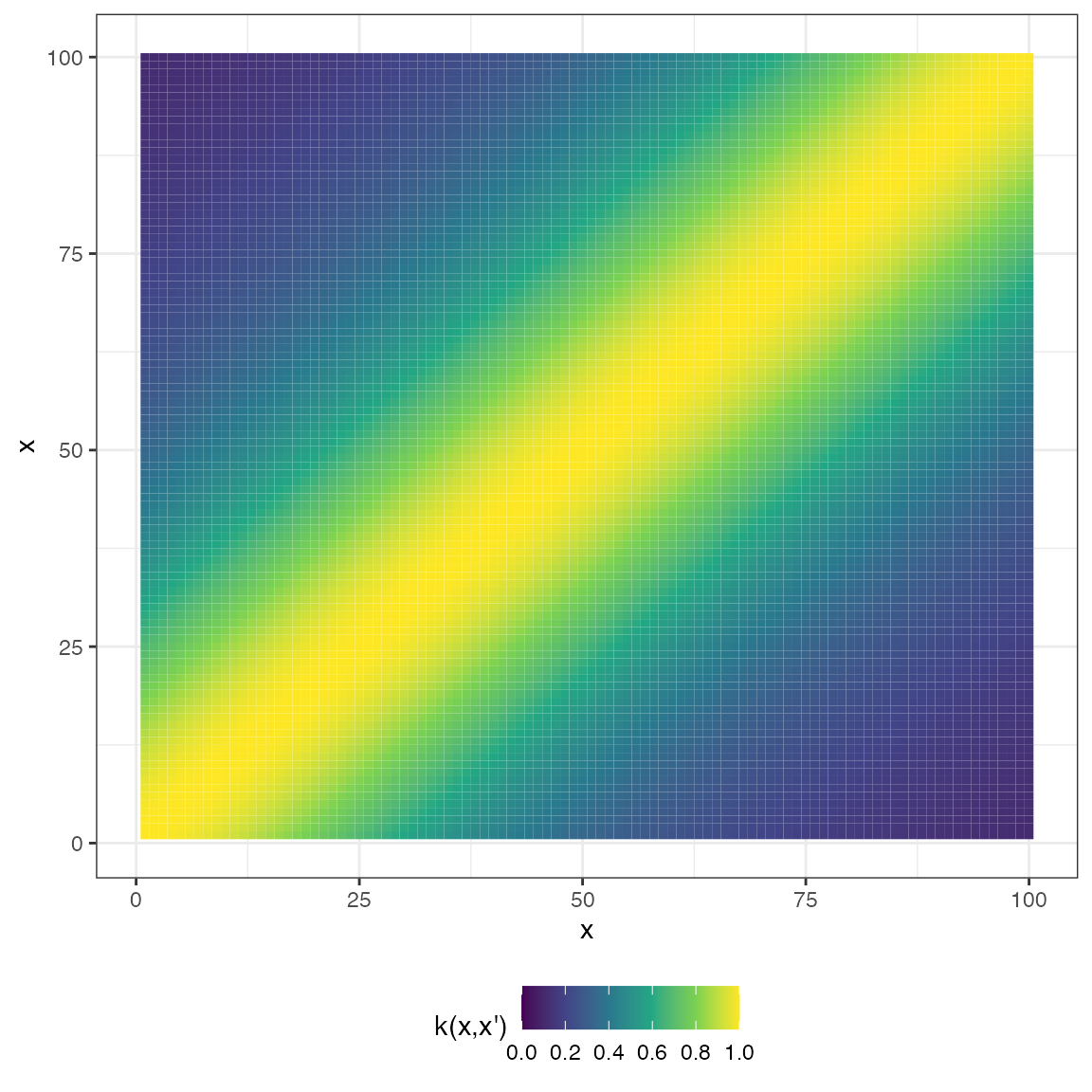

plot(mat_rat_quad, type = "matrix")

Periodic

\[ k(x, x') = \sigma^{2} \text{exp} \left( -\frac{2}{\mathcal{l}^{2}}\text{sin}^{2} \left( \pi\frac{|x - x'|}{p} \right) \right) \]

In tsgp, cov_periodic takes the following

arguments:

-

xa— vector of values -

xb— vector of values -

sigma— scalar denoting the variance. Defaults to1 -

l— scalar denoting the lengthscale. Defaults to1 -

p— scalar denoting the period. Defaults to1

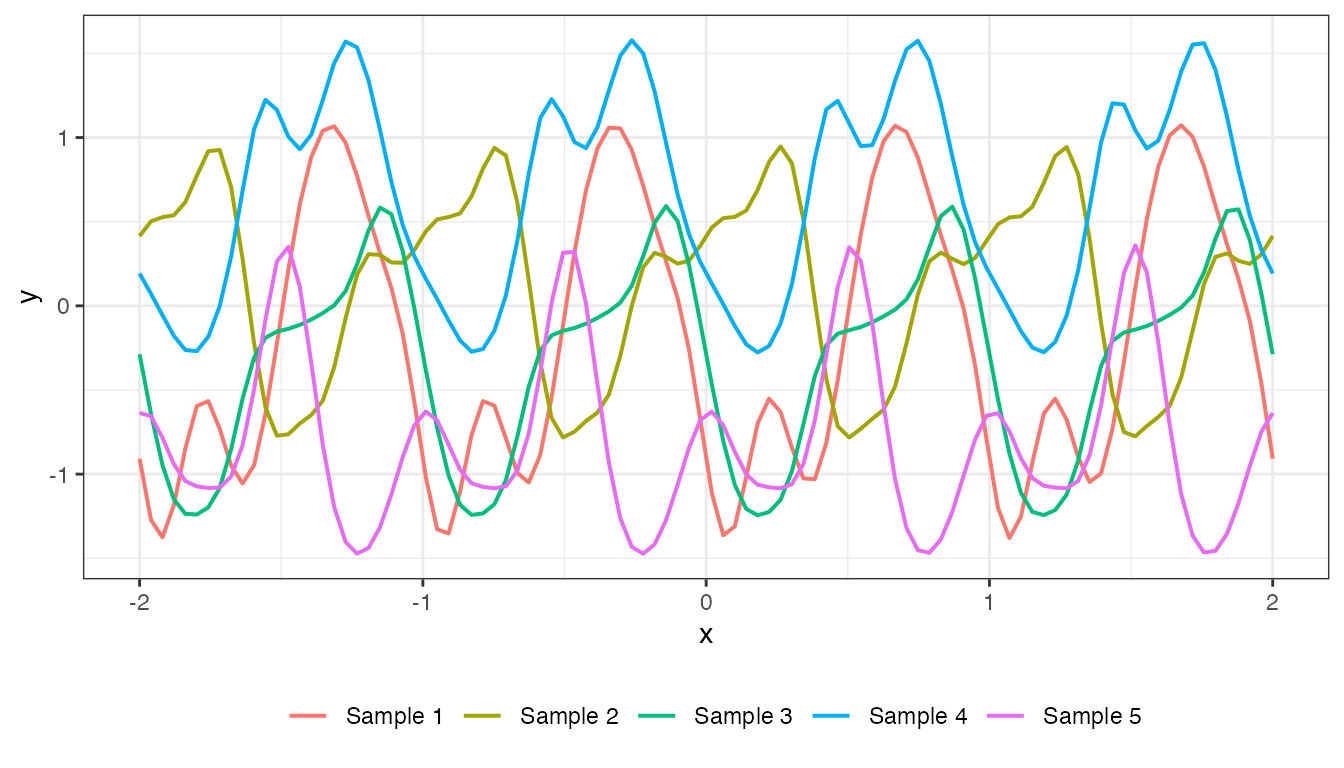

mat_periodic <- cov_periodic(x2, x2, 1, 1, 1)

plot(mat_periodic, x2, type = "prior", k = 5)

plot(mat_periodic, type = "matrix")

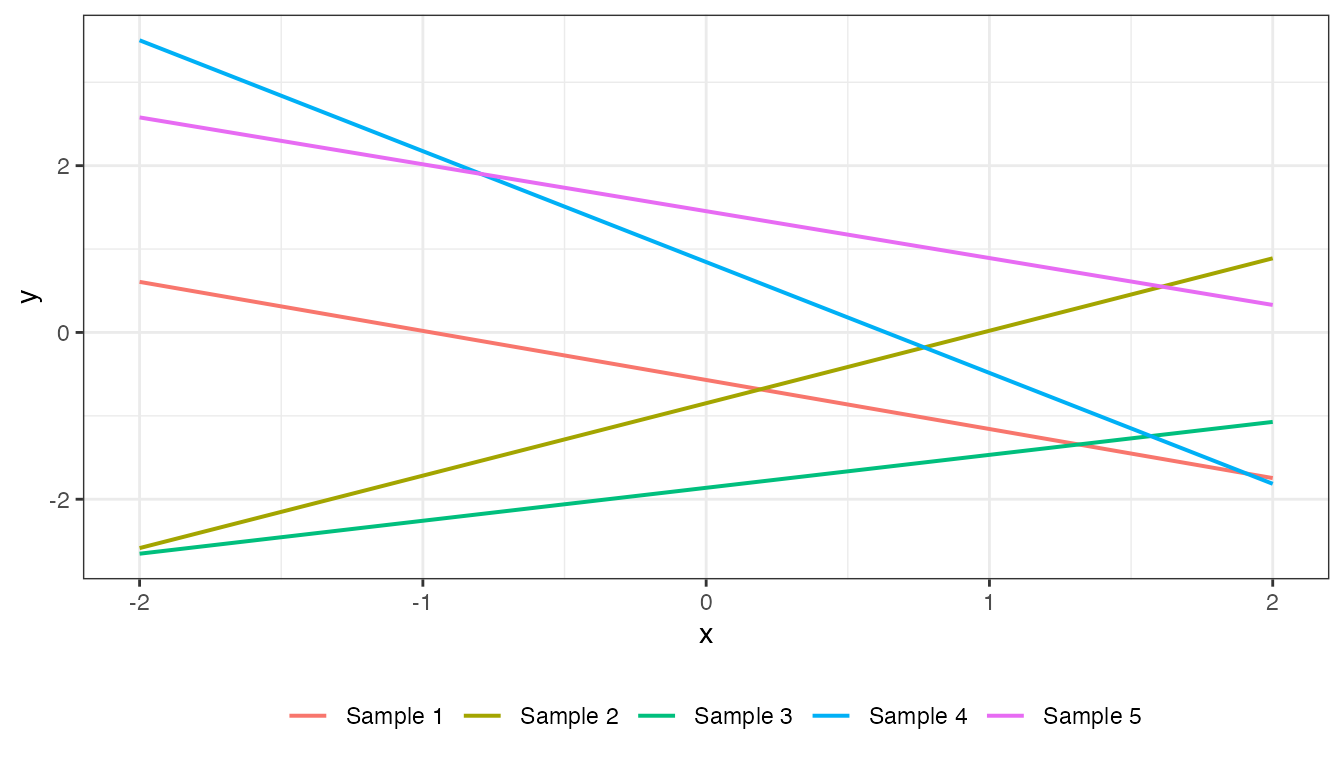

Linear

\[ k(x,x') = \sigma^{2}_{b} + \sigma^{2}_{v} (x−c)(x'−c) \]

In tsgp, cov_linear takes the following

arguments:

-

xa— vector of values -

xb— vector of values -

sigma_b— scalar denoting the constant variance. Defaults to1 -

sigma_v— scalar denoting the constant variance. Defaults to1 -

c— scalar denoting the offset. Defaults to1

mat_linear <- cov_linear(x2, x2, 1, 1, 1)

plot(mat_linear, x2, type = "prior", k = 5)

plot(mat_linear, type = "matrix")

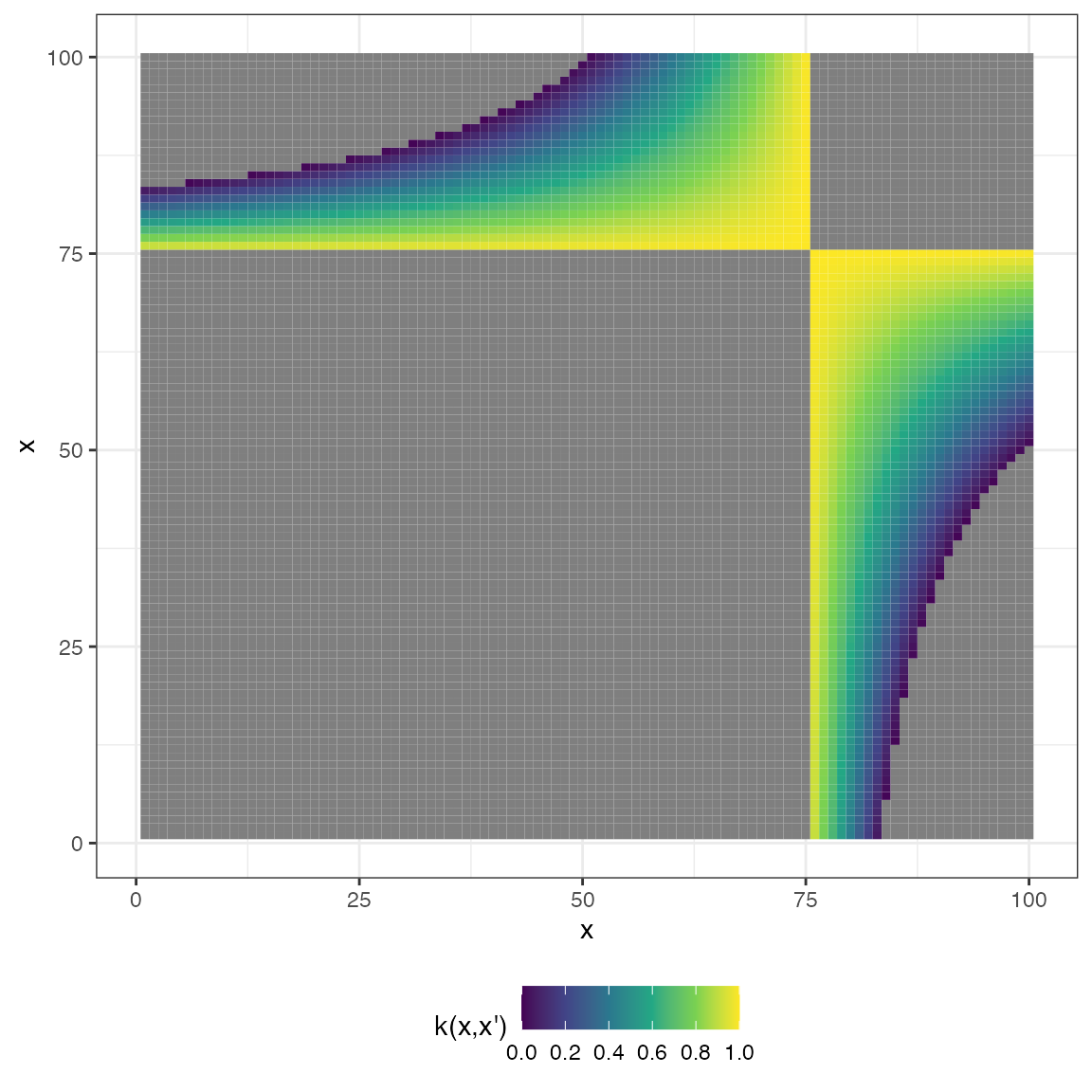

White noise

\[ k(x, x') = \sigma^{2}I_{n} \]

In tsgp, noise is handled within the core

GP function since it only applies to the covariance matrix

between observations. The GP function is discussed later in

this vignette.

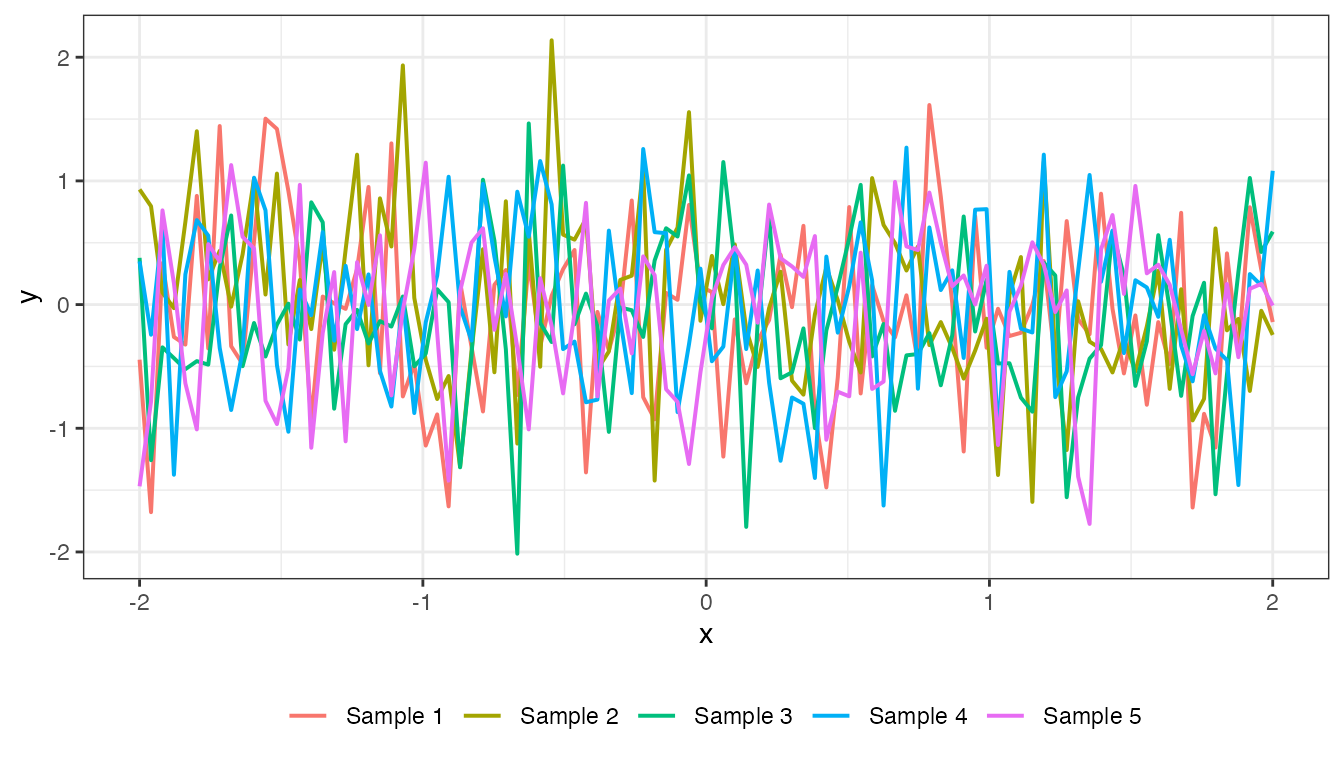

However, for visual comparison to the other covariance functions, here is what it looks like:

cov_noise <- function(x, sigma = 0.5){

X <- sigma * diag(length(x))

X <- structure(X, class = c("GPCov", "matrix"))

return(X)

}

mat_noise <- cov_noise(x2, 0.5)

plot(mat_noise, x2, type = "prior", k = 5)

plot(mat_noise, type = "matrix")

Combining covariance functions

Often in time-series analysis we need our models to capture multiple different statistical dynamics simultaneusly, such as trend, seasonality, and noise. It is quite easy to define a custom composite kernel function which either sums or multiplies different kernels:

CovSum <- function(xa, xb, sigma_1 = 1, sigma_2 = 1, l_1 = 1, l_2 = 1, p = 1){

X <- cov_exp_quad(xa, xb, sigma_1, l_1) +

cov_periodic(xa, xb, sigma_2, l_2, p)

X <- structure(X, class = c("GPCov", "matrix"))

return(X)

}Model fitting

The core function in tsgp to calculate the posterior

mean vector and covariance matrix is GP. GP

returns an object of class TSGP which is a list of the

input data, the posterior mean vector, and the posterior covariance

matrix. GP takes the following arguments:

-

x— vector of input data -

xprime— vector of data points to predict values for -

y— vector of values to learn from -

covfun— function specifying the covariance -

noise— scalar denoting the noise variance to add to the \((x, x)\) covariance matrix of observations. Defaults to0for no noise modelling -

...— hyperparameters to be passed tocov_function

Here is an example for a model which predicts values for a set of uniformally-distributed time points over the \([1-100]\) domain:

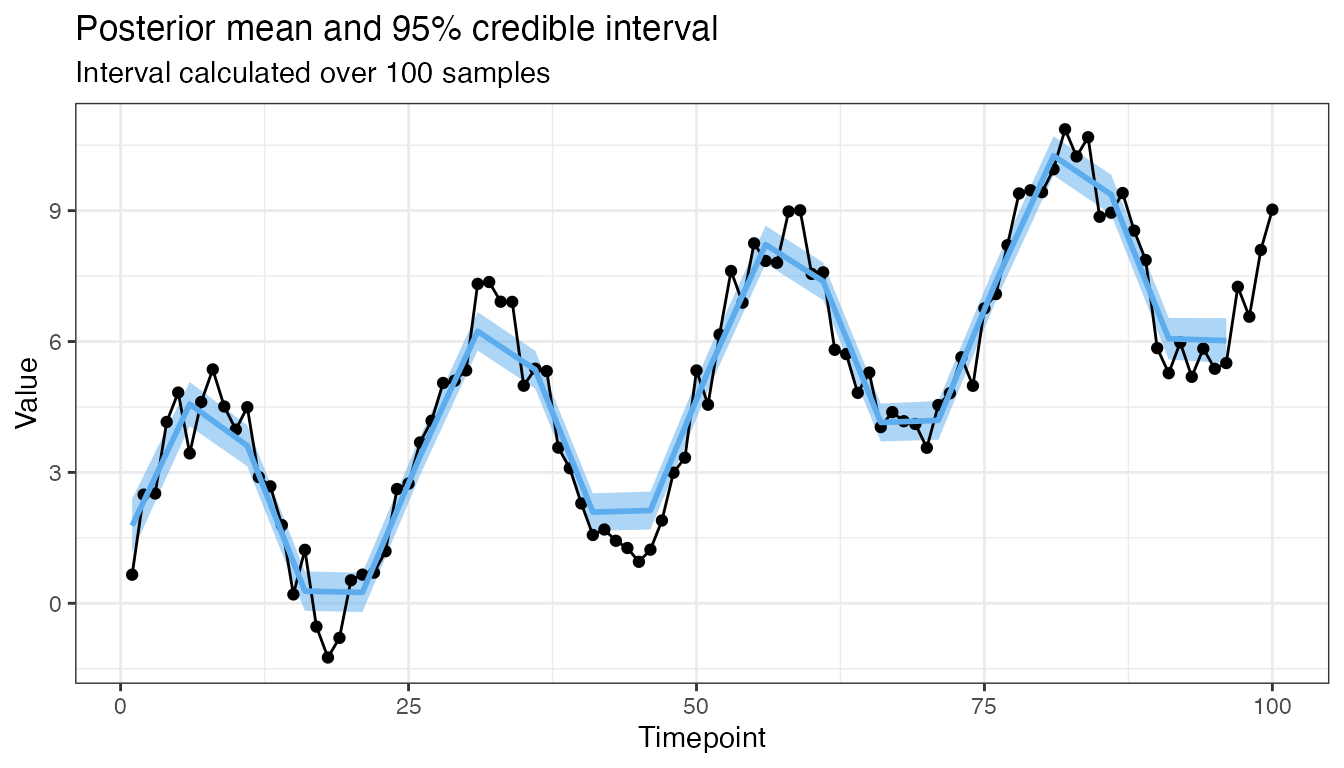

Model visualisation

We can easily visualise draws from the posterior distribution by

calling plot() on a TSGP object. The

plot() generic for TSGP takes only three

arguments:

-

x—TSGPmodel object -

prob— desired credible interval probability level. Defaults to0.95for a \(95\%\) credible interval -

draws— number of posterior draws to summarise over. Defaults to \(100\)

Here is an example:

plot(mod, 0.95, 100)

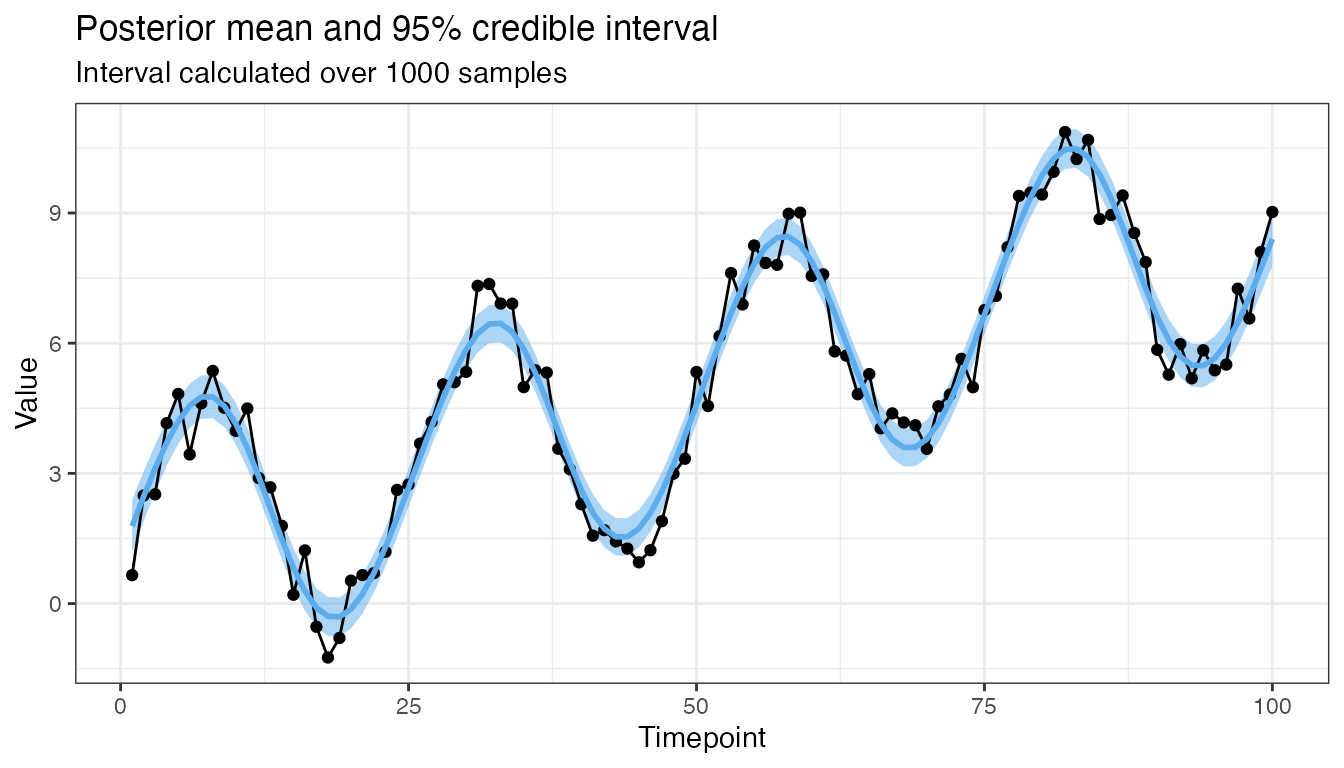

Here is another for a model which predicts for all time points but with \(1000\) draws:

mod2 <- GP(x1, x1, y, CovSum, 0.8,

sigma_1 = 5, sigma_2 = 1, l_1 = 75, l_2 = 1, p = 25)

plot(mod2, 0.95, 1000)

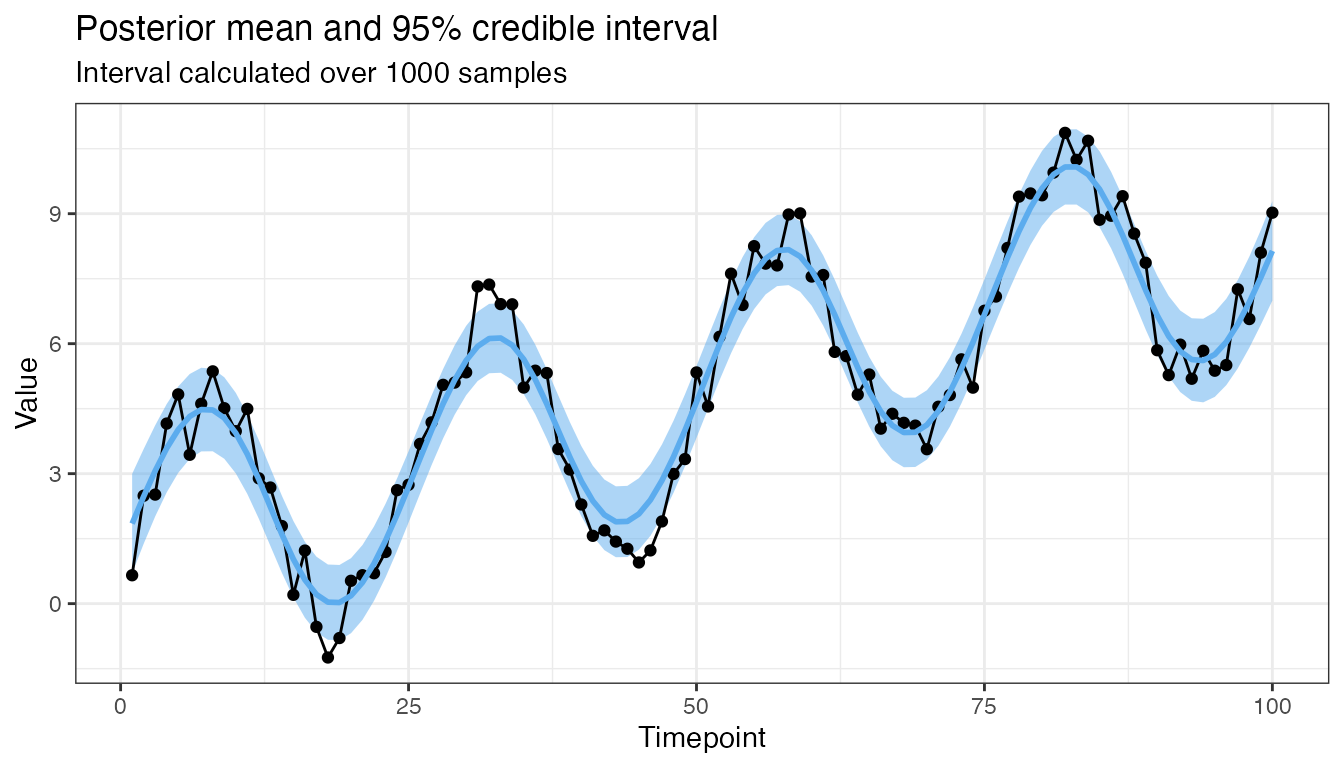

Need more uncertainty?

mod3 <- GP(x1, x1, y, CovSum, noise = 1.75,

sigma_1 = 5, sigma_2 = 1, l_1 = 75, l_2 = 1, p = 25)

plot(mod3, 0.95, 1000)

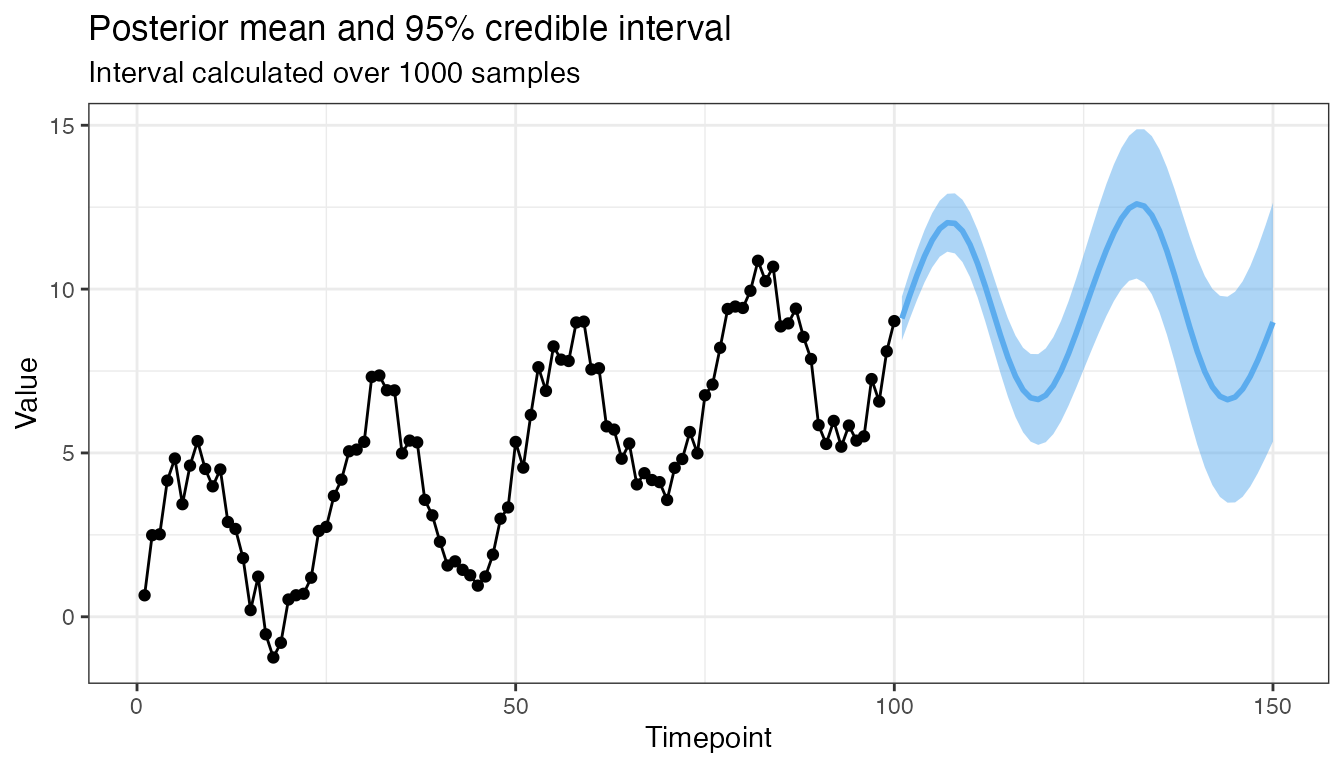

What about a short-range forecast?

mod4 <- GP(x1, 101:150, y, CovSum, 0.8,

sigma_1 = 5, sigma_2 = 1, l_1 = 75, l_2 = 1, p = 25)

plot(mod4, 0.95, 1000)